In April 1986, more than 150 student protesters on the University of California Berkeley campus were arrested with charges of felony and misdemeanors. Earlier that day, three protest groups on campus had held a rally, after which they set up fifteen plywood structures blockading the entrance to the administration building, in what public information officer Ray Colvig called “unorganized and uncooperative [demonstrations].” Onlookers threw bottles, stones and bricks, shouting angry cries as the arrested students were hauled away. While charges were dropped later that month, the students continued to fight tooth and nail for their cause: divestment in South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Divestment is defined as the reduction of assets from one business or governing body by another for financial, ethical, or political objectives. In short, a divestment is the opposite of an investment. Berkeley students were attempting to remove the college’s investments in companies dealing with the South African government. This sentiment, shared among many students, was quick to grow into a movement that spanned the entire country. Just a year earlier, a few dozen similarly minded anti-apartheid students staged a sit-in on the front steps of Berkeley’s Sproul Hall. The students, with little besides political passion and a few sleeping bags, rallied hundreds into joining them during their sit-in and thousands for midday protests. A banner above their steps called out their simple yet simultaneously complicated demands: END UC TIES TO APARTHEID. CALL TO DIVEST.

Historically speaking, student activism alone was not enough to halt apartheid. Rather, the de-investment campaign impacted South Africa only after the governments of major western nations (including the United States) got involved. Student activism alone can not stop a conflict without government support—although it can spur motion, like what happened at Berkeley in 1986.

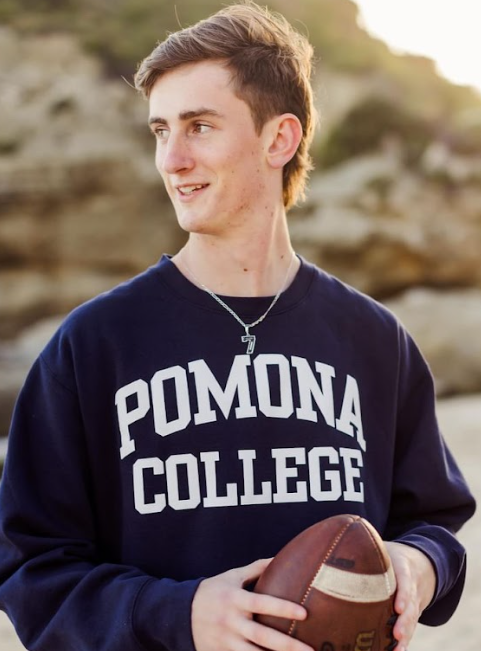

Now, just less than forty years later, student activism in protest to the war in Gaza has begun. On December 8th 2023, Claremont Colleges students staged the first of many sit-in protests, similar to the ones used to protest apartheid (albeit on a smaller scale). They demanded Pomona College divest endowment funds from firms that students say are benefitting weapons manufacturers and companies known to be aiding the Israeli war effort against Hamas in Gaza. In addition to divestment, the students also urged Pomona college officials to call for a cease-fire between the two warring factions.

Once again, student activist groups are leaning towards divestment as a strategy to find a resolution to the freshly born conflict–and it is easy to see why. The student-led movement of the early 1980s largely contributed to the United States’ 1986 divestment policy, which went on to play a major role in pressuring South Africa’s government into dismantling the apartheid system. If students in the ‘80s could prompt their schools (and eventually the government) to de-invest in South Africa, who is to say that students now, even amongst an increasingly hostile political climate, can not do the same against Israel? Quite bluntly, the answer to that not-so-rhetorical question lies in the quarrels and qualms of Washington’s foreign policy.

Israel has long been the most prominent recipient of US foreign aid, and although that aid has been put under increased scrutiny since the beginning of the conflict in Gaza, it is highly unlikely that either party, Democrats or Republicans, will pull out funding from Israel (much less sanction them). Why is this, when the two political parties seem to be on opposing sides of nearly every controversy nowadays? The truth is that both party platforms have historically maintained pro-Israel positions, continuing and even bolstering aid to the Jewish state.

Currently, the Democratic Party is facing a split on this wedge issue, with leaders such as President Biden and California Representative Brad Sherman arguing their support of the Jewish state and others their opposition. For example, a March 23 Gallup Poll found that a whopping 75% of Democratic voters disapprove of Israel’s military action in Gaza. Despite voter dissent however, its party platform has maintained its pro-Israel stance, with the narrow Democratic majority in the Senate approving $14 billion in aid for the nation in late February.

What is even more certain than the Democratic party platform’s support for Israel is the GOP’s disdain for Palestine. In the months since the October 7 attack and Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza, several conservative figureheads—including Florida Republican Michelle Salzman during a November debate in the Florida State Legistlature—have called for genocide against Palestinian civilians. When rhetorically asked how many more Palestinian civilians needed to die for a ceasefire deal to be reached, Salzman responded, “All of them”. This chilling sentiment runs deep in the Republican Party, eclipsing any and all opposition to Israel. Sure to say, student activists will not be getting any laws passed by either party that would limit the United States’ investments in its Middle Eastern ally any time soon.

While Democrats and Republicans may appear to be united on the issue of Israel, students and faculty at the Claremont Colleges are more divided than ever. Pomona College President Gabrielle Starr recently sent out an email to the faculty and community of the college regarding a student referendum held by the Associated Students of Pomona College (ASPC). This referendum, a non-binding, symbolic display of public opinion, pursued an academic boycott of Israel and divestment from all companies aiding the Jewish state. In the email, the college president expressed her concerns that the referendum could be perceived, by Jewish members of the college community, as antisemitic.

“For many years now, the only nation on which the ASPC has focused its activity is the world’s only Jewish state,” Starr wrote. “This singling out of Israel raises grave concerns about the referendum’s impact on members of our community [and] […] raises the specter of antisemitism.”

When the results of the referendum were released on February 22, 81.7 percent of students answered in the affirmative when asked if the college should divest from companies aiding Israel’s ‘apartheid system’. This fervent support for divestment has manifested itself in many ways. On April 5, chants of “Israel bombs, Pomona pays. How many kids will you kill today?” could be heard across campus as twenty student protestors were arrested by police officers—in riot gear and armed with tear gas and automatic AR-15 rifles—after storming President Starr’s office. All charges were dropped a few hours later, though Pomona students involved still faced suspension and an arrest on their record. If you’re interested in learning more about the Pomona protests, click here.

The violent putdown of political protests on college campuses now, in 2024, shows striking parallels to Berkeley almost four decades ago. Whether the community takes this as a sign that divestment has a chance ultimately depends on how these young activists intend on getting their message across and whether the campaign for divestment will be seen as peaceful or violent. As in 1986, events half a globe away have spurred a wave of student activism, yet have become the roots from which division stems on college campuses and the Claremont community as a whole.